硫化锌晶体有两种晶体结构:室温稳定的立方闪锌矿结构β-ZnS相和六方纤锌矿结构的介稳相α-ZnS。将β-ZnS热压制成的透明多晶陶瓷,具有优异的8~14 μm红外透过率、高熔点和高理化稳定性,在红外光学和红外探测等领域得到了广泛的应用[1~4]。近年来随着纳米粉体成本的降低,以纳米β-ZnS粉体为原料热压制备硫化锌透明陶瓷成为热点[3,5,6]。用化学法制备的硫化锌纳米粉体均为立方β-ZnS相[6],但是β-ZnS纳米晶的粒径小至一定尺寸时发生纳米尺寸诱导低温固态相变使立方相转变为六方相(即β→α)[2]。尺寸为10~15 nm的β-ZnS颗粒的相变温度低至400 ℃[7],使以β-ZnS纳米粉体为原料烧结制备的陶瓷含有六方α-ZnS。六方α-ZnS相的光学各向异性引起双折射和光散射,使ZnS陶瓷光学性能和其他性能降低[8]。避免生成六方α-ZnS相,已成为用纳米粉体热压制备ZnS透明陶瓷的难点。

研究者尝试用各种方法减少ZnS热压过程中生成的六方相。Li等[9]用水热法耗时10~50 h处理尺寸为4~10 nm的β-ZnS原料,在800 ℃烧结出立方相含量约为90%的硫化锌陶瓷。Durand等[2]在H2S气流中热处理β-ZnS纳米粉体,使其粒径达到~200 nm后在950 ℃热压出ZnS陶瓷;Yeo等[10]在550 ℃/10-4 Pa条件下真空热处理纳米ZnS至~300 nm,然后在950 ℃制备出透明β-ZnS陶瓷。以上的结果是增大纳米β-ZnS的粒径至亚微米级,以提高尺寸诱导低温相变的阈值温度。但是,纳米粉体粒径的分布较宽,在热处理中部分纳米β-ZnS粉体就已经发生相变,且长时间热处理使成本显著提高。因此,以β-ZnS纳米粉体为原料制备没有六方α-ZnS相的硫化锌透明陶瓷极为困难。

本文以β-ZnS纳米粉体为原料并添加卤化钾KX (X = Br、I、Cl)纳米晶,进行一步热压制备硫化锌透明陶瓷。研究KBr对烧结中晶粒生长和相变的影响,对比添加KI、KCl的效果并结合Br-、I-和Cl-阴离子半径揭示卤化钾抑制β-ZnS纳米粉体低温相变的机理。

1 实验方法

实验用ZnCl2和CS(NH2)2均为分析纯。用化学均相沉淀法合成ZnS纳米粉体:在室温将6.82 g(0.050 mol)的ZnCl2和5.70 g (0.075 mol)的CS(NH2)2分别溶于50.0 mL和150.0 mL的去离子水中,制得浓度为1.0 mol/L的ZnCl2溶液和0.5 mol/L的CS(NH2)2溶液。在搅拌条件下将2.0 mol·L-1的NaOH溶液逐滴加入到ZnCl2溶液中,溶液清澈后再滴入30.0 mL丙三醇(99.5%)(作为粘度调节剂);然后将CS(NH2)2溶液注入到上述澄清溶液中,制备出物质的量比为S/Zn = 1.5的均匀前驱体溶液。将前驱体溶液过滤除去不溶性杂质后转移到烧瓶中,在85 ℃水浴中搅拌120 min直至出现白色沉淀。反应完成后,将烧瓶置于0 ℃的冰水中快冷,使沉淀颗粒停止生长。过滤出沉淀物并用去离子水和乙醇充分清洗,然后将其在70 ℃真空干燥得到ZnS粉体。

将5.00 g干燥ZnS粉体分别与0.5%、1.5%、3.0%(质量分数)的KBr纳米晶(平均粒径(50 ± 10) nm)混合,将三份混合料分别装入涂有BN粉体的石墨模具中置于气氛热压炉中在氩气气氛中热压烧结:氩气的压力为30.0 MPa、升温速率为10 ℃/min、烧结温度为830 ℃ ± 10 ℃,烧结时间为1.0 h。为了对比研究,将3.0%的纳米晶KX (X = Cl, I)分别与5.0 g ZnS纳米粉体混合料在相同条件下热压烧结。将制备出的ZnS陶瓷抛光用于测试。上述实验所用KX纳米晶制法为:将浓度为0.2 mol/L的相应卤化钾盐的乙醇-水溶液滴加到温度为280~300 ℃的石英玻璃片上,溶液快速挥发后即获得KX纳米晶[11]。

用D/max-3C X射线衍射仪(XRD, Rigaku)测试样品的XRD谱,使用Cu Kα (0.154178 nm)辐射;用扫描电子显微镜(SEM, Hitachi S-570)和附带的X射线光电子能谱(EDX)表征陶瓷的微观结构和成分;用Nicolet Nexus FTIRS光谱仪测试样品的红外透过性能,用光致荧光谱仪(Hitachi F-4600)分析发光特性;用Archimedes法测量陶瓷密度。

2 结果和讨论

2.1 ZnS粉体的形貌和物相组成

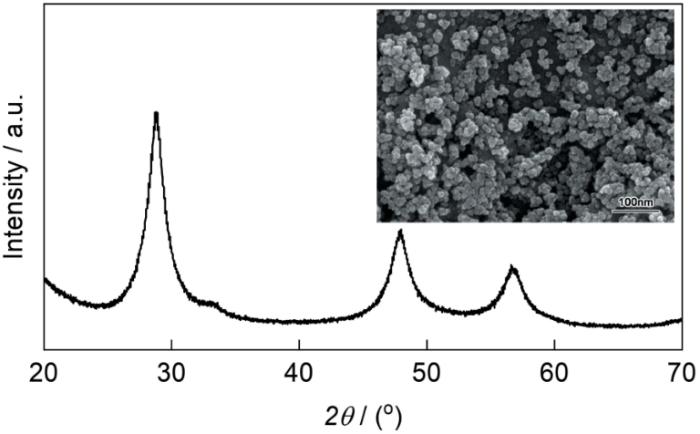

图1

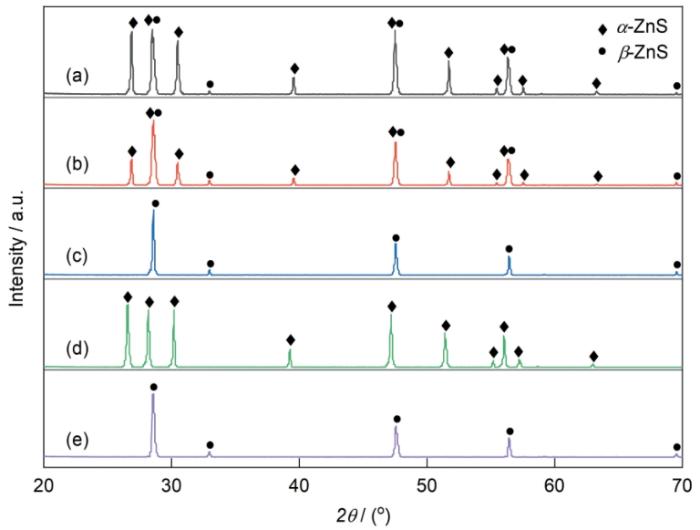

图2给出了添加不同量的KX (X = Br、I、Cl)制备的ZnS透明陶瓷的XRD谱。KBr纳米晶的添加量(质量分数,下同)分别为0.5%、1.5%和3.0%,KCl和KI纳米晶的添加量为3.0%。图2中立方相β-ZnS的衍射峰用“●”标记;标记为“◆”位于2θ ≈ 26.9°、28.5°、30.5°、39.6°、47.6°、51.8°、55.5°、56.4°和57.6°的衍射峰分别对应六方α-ZnS的(100)、(002)、(101)、(102)、(110)、(103)、(200)、(112)和(201)晶面(JCPDS: 36-1450)。图2a表明,KBr添加量为0.5%制备的陶瓷ZnS-A为六方α-ZnS相,因为β-ZnS纳米粉体的尺寸诱导的低温相变温度低于烧结温度830 ℃[12];对比图2b、c可见,随着KBr加入量由1.5%增加到3.0%位于2θ = 26.9°、30.5°的峰逐渐降低,表明ZnS-B中的六方α-ZnS相减少,直至陶瓷ZnS-C完全不含六方α-ZnS相。在对比实验中,添加剂换做KI和KCl,制备出的陶瓷的XRD谱在图2d,e中给出,可见添加3.0% KCl制备的ZnS-D主晶相是α-ZnS;而含3.0% KI的ZnS-E中没有六方α-ZnS。这个结果表明,3.0%的KBr和KI可抑制α-ZnS相的生成,而KCl却促进了六方相的生成。KCl与KBr、KI同属于卤化钾盐,只是阴离子不同,其对热压过程中尺寸诱导低温β→α相变的不同影响可能与阴离子的半径有关。

图2

图2

添加不同量、不同KX (X = Br、I、Cl)的ZnS透明陶瓷的XRD谱

Fig.2

XRD patterns of ZnS transparent ceramics with various amount of additive KX (X = Cl, Br, I): (a) ZnS-A: 0.5%KBr, (b) ZnS-B:1.5%KBr, (c) ZnS-C:3.0%KBr, (d) ZnS-D: 3.0%KCl, (e) ZnS-E: 3.0%KI

2.2 ZnS陶瓷的微观形貌和成分

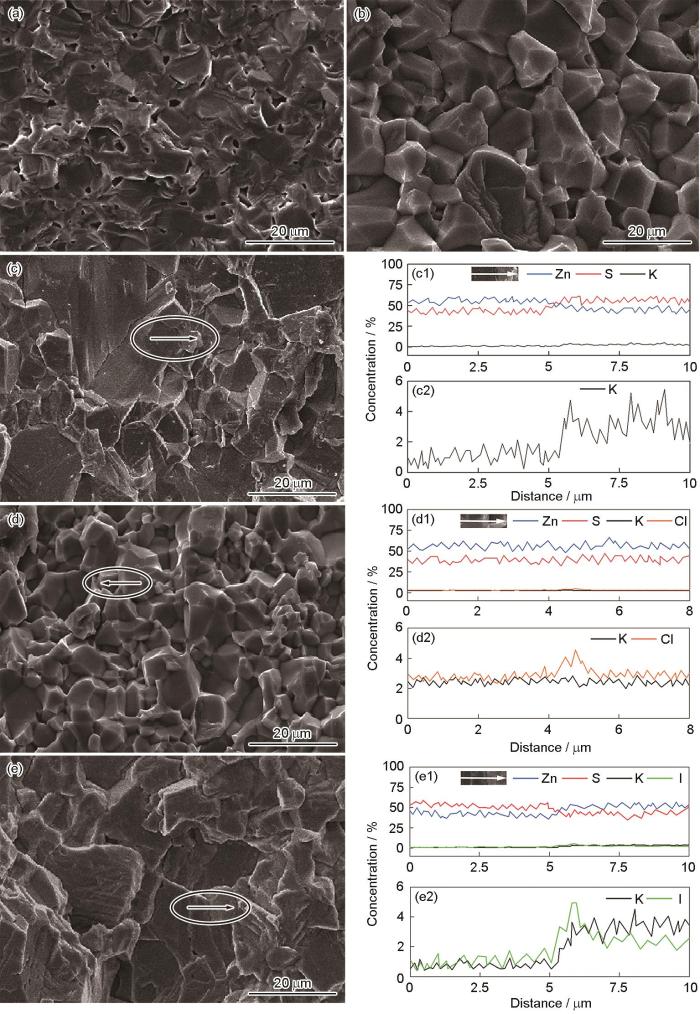

图3给出了使用不同KX添加量制备的ZnS陶瓷的微观形貌和EDS能谱,其中硫化锌陶瓷ZnS-A、ZnS-B、ZnS-C、ZnS-D和ZnS-E的标示与图2相同。图3a表明,添加0.5% KBr的ZnS-A陶瓷其平均晶粒尺寸约5.0 μm,因残余气孔较多相对密度为89%;ZnS-B陶瓷(图3b)晶粒的粒径约为12.0 μm,相对密度为98%;ZnS-C陶瓷(图3c)的晶粒尺寸约为20.0 μm,相对密度为99.0%。随着KBr添加量的增加,陶瓷的晶粒增大、致密度提高。其原因是KBr纳米晶(~50 nm)[11]在低于KBr熔点(Tm = 734.0 ℃)的温度熔化,产生的液相加速了原子扩散,有利于陶瓷晶粒的长大和烧结密度的提高。纳米晶KCl (Tm = 770 ℃)和KI (Tm = 681 ℃)的液相也促进了ZnS-B、ZnS-C的烧结致密化。比较图3c、d、e可见,添加同量(3.0%)的KBr、KCl和KI制备的ZnS-C、ZnS-D、ZnS-E陶瓷其平均粒径R由大到小的排序为RE(~25.0 μm,下标E对应ZnS-E,下同) ˃ RC (~20.0 μm) ˃ RD(~5.0 μm),陶瓷的相对密度ρ大小的排序为

图3

图3

添加不同量、不同KX (X = Br、I、Cl)制备的ZnS透明陶瓷的微观形貌

Fig.3

SEM images of ZnS transparent ceramics with various amount of additive KX (X = Cl, Br, I) (a) ZnS-A: 0.5%KBr, (b)ZnS-B: 1.5%KBr, (c) ZnS-C: 3.0%KBr, (d) ZnS-D: 3.0%KCl, (e) ZnS-E: 3.0%KI; (c1-e1) EDS energy spectra of elements map in (c-e), (c2-e2) the enlarged views of K and X in (c1-e1)

为了揭示KX在烧结中的作用,分析了ZnS-C、ZnS-D、ZnS-E陶瓷的成分。图3c1、c2列出了图3c中椭圆标示的典型区域的EDS能谱对应的Zn、S和K元素在晶界附近的分布(仪器不支持Br元素EDS能谱),其中图3c2为c1中K元素分布的放大图。由图3c1可见,椭圆区域中较大晶粒显示S元素缺失,而小晶粒则富含S;K元素分布在小晶粒中,而大晶粒中的K(在误差范围内)少得可忽略。K、S成分的差异表明,图3c椭圆区域中两个典型晶粒的生成过程可能不同,与KBr促进晶粒生长和抑制六方α-ZnS相的生成有关。图3d1、d2、e1、e2分别给出了ZnS-D、ZnS-E典型区域的EDS能谱,可见添加KCl的ZnS-D陶瓷其典型晶粒的晶界两侧K、Cl元素的成分分布基本相同,只是在晶界处出现少量Cl聚集,两个晶粒均缺失S,表明ZnS-D中两晶粒的生成过程相同,即只有一种晶粒生成机制。而加入KI的ZnS-E其两晶粒晶界两侧的成分分布不同,其中I、K元素在小晶粒中富集,大晶粒则缺失S,表明与ZnS-C类似ZnS-E陶瓷也有两种生成ZnS晶粒的机制。

2.3 纯立方相ZnS陶瓷生成的机理

图4

图4

KBr抑制纳米β-ZnS低温相变机理的示意图

Fig.4

Schematic illustration of mechanism on inhibiting low-temperature phase transition of ZnS nanocrystals (a) mixture of β-ZnS and KBr, (b) KBr molecular layer via spontaneous diffusion, (c) KBr liquid molecular layer and α-ZnS nucleus on ZnS nanopartical surface, (d) ZnSKBr melt dissolving α-ZnS nuclues, (e) β-ZnS nuclei from ZnSKBr melt, (f) β-ZnS grains from melt

将KBr纳米晶与β-ZnS纳米粉体均匀混合(图4a)后置于高温热压炉中,升温至300~400 ℃时KBr分子扩散到ZnS纳米颗粒表面形成分子层(图4b)。按照文献[13,14]中提出的固态分子层模型,这种分子层是由Br-阴离子构成的紧密堆积的单/多分子层,K+分布在Br-空隙中。这种分子层的形成,是一种热力学自发过程[14~16]。异质分子层可抑制表面原子的振动使载体的表面能降低以提高纳米颗粒的稳定性[17~19]。例如,在350 ℃表面分布水分子粒径为3 nm的β-ZnS纳米粒子不出现尺寸诱导的β→α相变[20],但是粒径为7 nm表面清洁的β-ZnS纳米粒子在相同条件下出现六方α-ZnS相形核[21]。因此,图4a~c中的KBr纳米晶在约300~400 ℃自发形成分子层可提高β-ZnS纳米粒子的稳定性,避免发生纳米尺寸诱导的相变[7,12];在图4d中,在炉温继续从400 ℃提高到734 ℃(KBr熔点)的过程中,KBr纳米晶熔成熔体(纳米晶的熔点低于734 ℃),液相KBr继续扩散附着在所有粒子表面,固态扩散分子层未覆盖的纳米粒子表面进而被KBr熔体分子完全覆盖,类似于水分子或离子液体使ZnS纳米粒子的稳定性提高[20,22],KBr熔体成为继固态分子层后使ZnS纳米粒子的相稳定性提高和抑制低温β→α相变发生的基础。本文快速终止烧结实验并未发现生成了α-ZnS相,表明其抑制相变的有效性。同时,KBr液相能显著促进晶粒的生长,与图3a~c中晶粒尺寸随着KBr添加量的增加而增大的结果一致。

同时,在高温下ZnS易于溶解在卤化物熔体中[23~25],故卤化钾熔体能降低纳米β-ZnS的表面能,还能溶解六方晶核抑制/阻断六方α-ZnS晶相的生成(图4d)。纳米β-ZnS粒子发生低温相变形成六方α-ZnS晶体的过程,遵循典型的定向附着(Oriented attachment, OA)机制[12,26],即只有具有相同晶体学取向的ZnS纳米粒子才能结合生成较大的六方相晶粒,其驱动力为纳米晶结合后表面能的减小,并在生成无位错晶核后开始生长[27],这与ZnS晶体基于螺位错和层错参与的周期性滑移机制实现相变完全不同[28]。这意味着,在烧结过程中生成六方α-ZnS相需先生成晶核,然后按照OA机制长大生成六方晶粒。表面含ZnO(六方结构)的β-ZnS纳米粒子热处理后生成大量六方α-ZnS相的结果表明,OA机制符合实际[29]。考虑到纳米尺寸的六方α-ZnS的生成由β-ZnS粒子表面的成核控制[12],在烧结升温过程中附着在表面的KBr液相使β-ZnS纳米粒子表面难以存在六方相的形核位,即使部分未覆盖KBr分子的表面可以生成六方核(六方晶核一般定义为3~4层按照ABABAB堆垛的原子层[12]),随后也会被流动的KBr液相溶解。总之,KBr熔体附着在β-ZnS纳米粒子表面使其相稳定性提高,并溶解了β-ZnS粒子表面生成的六方晶核,阻断了β-ZnS粒子按照OA机制生成六方相的形核,从而抑制了ZnS纳米粉体的低温尺寸诱导相变,其机理在图4b~f中给出。

KBr熔体的形成,可解释图3c中的成分分布和晶粒生成机制[24,25]。按照图4e、f给出的结果,随着温度继续升高KBr溶液对六方晶核和ZnS晶粒表面物质的溶解能力随之提高,进而形成ZnSKBr四元素构成的熔体,这种熔体冷却或饱和时,ZnS在有利的位置成核和析出。由于最高烧结温度830 ℃远低于ZnS晶体的相变温度1020 ℃,按照Oswald's析晶规则只能析出室温稳定相β-ZnS [24]。析出相的典型特点是夹带高温熔体组分K且ZnS富含S组分[30]。因此,图3c中富含S和K元素的小晶粒是由高温熔体析出的β-ZnS相晶粒;图3c中长大的大晶粒是高温作用的结果,其成分显著缺S或富Zn[31]。其原因是,S空位VS的形成能低于Zn空位VZn的形成能[32],使高温下的ZnS陶瓷缺失S。这就是图3c给出的ZnS-C陶瓷中两种晶粒(均为β-ZnS相)的生成机理。

图2表明,KI和KBr均能抑制六方相的生成,ZnS-E也是纯立方β-ZnS相陶瓷,但是加入3.0% KCl制备的ZnS-D陶瓷却是六方α-ZnS相。这表明KCl的作用与KBr和KI的作用相反。根据图4给出的机理,KX熔点的不同并不影响ZnS陶瓷的相成分,KX抑制或促进相变主要与Br-、I-以及Cl-离子半径的尺寸有关。根据文献[33]中的X-阴离子半径数据:I-(VI)(离子半径

2.4 ZnS透明陶瓷的光致发光谱和红外光谱

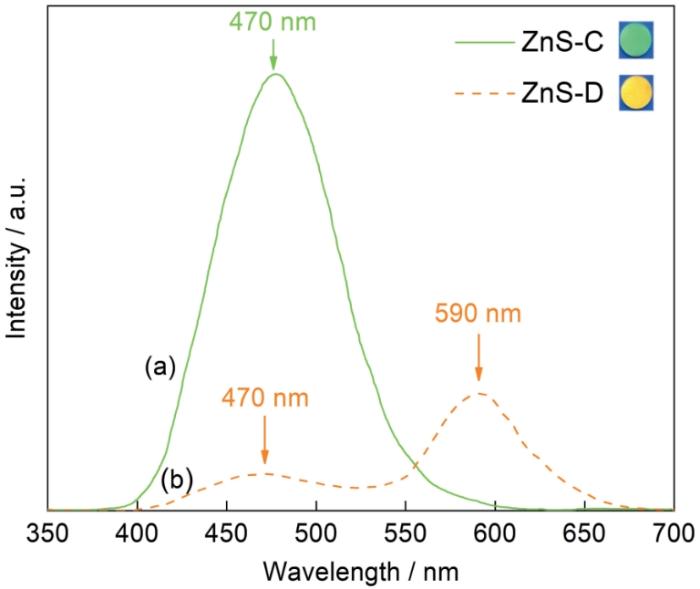

图5给出了在365 nm紫外光激发下ZnS-C(3%KBr)和ZnS-D(3%KCl)陶瓷的光致发光谱。由图5可见,在ZnS-D的谱中590 nm处出现较宽的黄色发光峰(峰位),此黄光是纤锌矿α-ZnS的离子空位与相异缺陷的复合发光[37]。位于ZnS-C样品谱中的470 nm处的绿色发光峰,可归因于闪锌矿β-ZnS中阳离子空位VZn的自激发光[37]。在ZnS-D的谱中470 nm处也出现了较宽的发光峰,是ZnS-D中少量的β-ZnS晶粒所致,与图2给出的XRD谱一致;两个样品都没有近带边发射[38],表明ZnS样品中晶粒的结晶质量显著低于同类单晶。ZnS-D样品的黄色发光意味着其缺陷较多,表明KCl扩散进入了晶格,不能保持在β-ZnS粒子表面稳定其相结构,并最终使六方相得以生成。发光测试结果表明,在烧结过程中KBr未进入ZnS-C陶瓷晶粒的晶格,间接支持了KBr纳米晶抑制六方相α-ZnS生成的机制。

图5

图5

紫外光(365 nm)激发ZnS陶瓷的光致发光谱

Fig.5

PL spectra of ZnS ceramics under 365 nm UV excitation at room temperature (Insert: luminous samples)

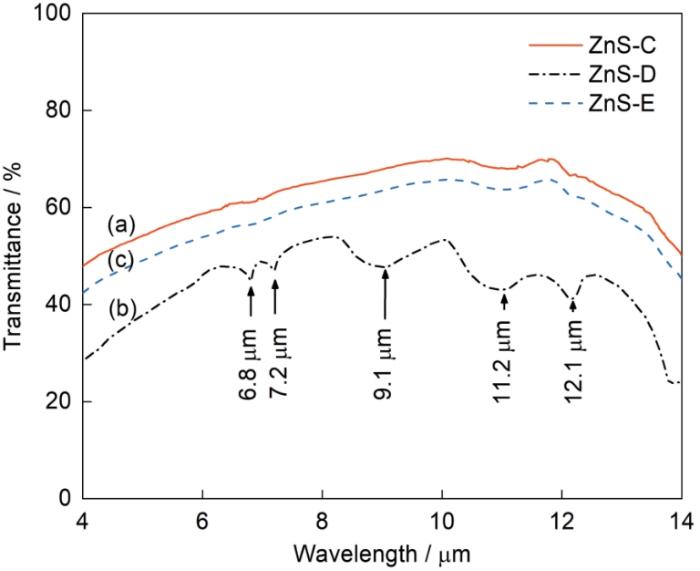

图6给出了ZnS-C、ZnS-D和ZnS-E在红外波段的透过率曲线,样品的厚度均为(1.0 ± 0.1) mm。由图6a可见,在4~14 μm波段ZnS-C的最高透过率为70.1%@10.1 μm,平均透过率为61.5%,低波长(< 8 μm)段较低的透过率与残余孔隙和痕量杂质有关[39]。位于12.1 μm附近较宽的弱吸收峰和11.2 μm附近的弱吸收峰,分别为痕量氧导致的Zn-O和S-O吸收峰[39,40]。图6c对应的ZnS-E的红外透过曲线与ZnS-C的类似,其最高透过率为65.7%@10.0 μm,平均透过率51.2%比ZnS-C陶瓷的低,与两者致密度的差异有关。同时也表明,KI和KBr不影响硫化锌透明陶瓷的红外性能。图6b对应的ZnS-D透明陶瓷的平均透过率较低(约为53.8%),在12.1 μm和11.2 μm附近也出现了较强的宽吸收峰。位于9.1 μm的较宽强吸收带以及6.8 μm和7.2 μm处的小吸收峰,是C=O和碳酸根的吸收峰[8,41,42]。在ZnS-D陶瓷的烧结过程中发生了β→α相变,相变时的晶格变化可导致模具的碳扩散进入晶格和晶界并生成了碳酸盐。

图6

图6

ZnS透明陶瓷(~1.0 mm)的红外透过光谱

Fig.6

IR spectra of as-sintered ZnS transparent ceramics (a) ZnS-C, (b) ZnS-D, (c) ZnS-E

3 结论

(1) 用化学均相沉淀法合成纳米β-ZnS粉体并添加KBr、KI和KCl纳米晶,模压后在氩气环境中热压,可制备透明ZnS陶瓷。

(2) KBr和KI纳米晶能促进晶粒生长和提高纳米β-ZnS粉体的相稳定性,并抑制烧结过程中尺寸诱导的低温相变,而KCl纳米晶促进了原料粉体烧结中的β→α相变。

(3) KBr和KI对应的阴离子大于S2-,较高的晶格扩散势垒使其难以在烧结温度下进入β-ZnS晶格,自发的分子扩散、熔体包裹使原料粒子的表面能降低,高温溶液可将六方晶核溶解,能抑制热压中纳米尺寸诱导立方闪锌矿粉体的β→α相变。

参考文献

Materials development and potential applications of transparent ceramics: a review

[J].

New insights in structural characterization of transparent ZnS ceramics hot-pressed from nanocrystalline powders synthesized by combustion method

[J].

Highly IR transparent ZnS ceramics sintered by vacuum hot press using hydrothermally produced ZnS nanopowders

[J].

Progress in infrared transparencies under opto electro thermo and mechanical environments

[J].In recent years, there has been a growing interest and research focus on infrared optical thin films as essential components in infrared optical systems. In practical applications, extreme environmental factors such as aerodynamic heating and mechanical stresses, electromagnetic interferences, laser interferences, sand erosions, and rain erosions all lead to issues including cracking, wrinkling, and delaminations of infrared thin films. Extreme application environment imposes stringent requirements on functional films, necessitating high surface hardness, stability, and adhesion. Additionally, for multispectral optical transmissions, infrared optical thin films are expected to exhibit high transmittance in the visible and far-infrared wavelength bands while possessing tunability and optical anti-reflection properties in specific wavelength ranges. Electromagnetic shielding requires superior electrical performance, while resisting laser interference demands rapid phase change capabilities. This paper focuses on current research progresses in infrared optical thin films under extreme conditions such as opto, electro, thermos and mechanical environments. Table of Contents Graphic gives detailed outline. Future opportunities and challenges are also highlighted.

Transparent and luminescent ZnS ceramics consolidated by vacuum hot pressing method

[J].

Microstructural and optical properties of the ZnS ceramics sintered by vacuum hot-pressing using hydrothermally synthesized ZnS powders

[J].

Size-induced transition-temperature reduction in nanoparticles of ZnS

[J].

Densification behavior, phase transition, and preferred orientation of hot-pressed ZnS ceramics from precipitated nanopowders

[J].

Hot-pressing of zinc sulfide infrared transparent ceramics from nanopowders synthesized by the solvothermal method

[J].

Sintering and optical properties of transparent ZnS ceramics by pre-heating treatment temperature

[J].

Influence of NaX (X = Cl, Br, I) additive on phase composition, thermostability and high infrared performances of γ-La2S3 transparent ceramics

[J].

Size-dependent phase transformation kinetics in nanocrystalline ZnS

[J].Nanocrystalline ZnS was coarsened under hydrothermal conditions to investigate the effect of particle size on phase transformation kinetics. Although bulk wurtzite is metastable relative to sphalerite below 1020 degrees C at low pressure, sphalerite transforms to wurtzite at 225 degrees C in the hydrothermal experiments. This indicates that nanocrystalline wurtzite is stable at low temperature. High-resolution transmission electron microscope data indicate there are no pure wurtzite particles in the coarsened samples and that wurtzite only grows on the surface of coarsened sphalerite particles. Crystal growth of wurtzite stops when the diameter of the sphalerite-wurtzite interface reaches approximately 22 nm. We infer that crystal growth of wurtzite is kinetically controlled by the radius of the sphalerite-wurtzite interface. A new phase transformation kinetic model based on collective movement of atoms across the interface is developed to explain the experimental results.

Dispersion capacities of KCl and NaCl in zeolites

[J].

KCl、NaCl在分子筛载体上的分散阈值研究

[J].

Spontaneous monolayer dispersion of oxides and salts onto surfaces of supports: applications to heterogeneous catalysis

[J].

7Li MAS NMR studies on LiCl/γ-Al2O3

[J].

LiCl/γ-Al2O3的7Li MAS NMR研究

[J].

Recent conceptual advances in the catalysis science of mixed metal oxide catalytic materials

[J].

Increase in thermal stability induced by organic coatings on nanoparticles

[J].

Size-dependent melting of silica-encapsulated gold nanoparticles

[J].We report on the size dependence of the melting temperature of silica-encapsulated gold nanoparticles. The melting point was determined using differential thermal analysis (DTA) coupled to thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) techniques. The small gold particles, with sizes ranging from 1.5 to 20 nm, were synthesized using radiolytic and chemical reduction procedures and then coated with porous silica shells to isolate the particles from one another. The resulting silica-encapsulated gold particles show clear melting endotherms in the DTA scan with no accompanying weight loss of the material in the TGA examination. The silica shell acts as a nanocrucible for the melting gold with little effect on the melting temperature itself, even though the analytical procedure destroys the particles once they melt. Phenomenological thermodynamic predictions of the size dependence of the melting point of gold agree with the experimental observation. Implications of these observations to the self-diffusion coefficient of gold in the nanoparticles are discussed, especially as they relate to the spontaneous alloying of core-shell bimetallic particles.

Preparation and characterization of surface-coated ZnS nanoparticles

[J].

Molecular dynamics simulations, thermodynamic analysis, and experimental study of phase stability of zinc sulfide nanoparticles

[J].

Onset of sphalerite to wurtzite transformation in ZnS nanoparticles

[J].

Electroactive phase nucleation and isothermal crystallization kinetics in ionic liquid-functionalized ZnS nanoparticle-ingrained P(VDF-HFP) copolymer nanocomposites

[J].Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (P(VDF-HFP))-based copolymer nanocomposites are prepared by blending with hydrophobic ionic liquid-functionalized ZnS nanoparticles. Different characterization techniques such as X-ray diffraction, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, transmission electron microscopy and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) are employed to investigate the effect of the nano-additives to the conformational changes of copolymer chain segments before and after the melt crystallization. Isothermal crystallization kinetics of the nanocomposites are studied using DSC at different crystallization temperatures. Analysis of the experimental data reveals that the functionalized nanoparticles in nanocomposites gradually retard the crystallization rate through strong dipole-dipole interaction, but accelerates the nucleation rate, providing a large number of heterogeneous nucleation sites. However, at higher loading, they substantially restrict the crystal growth rate, leading to the formation of a large number of imperfect crystallites and a consecutive reduction in overall crystallinity. Different nucleation parameters such as initial laminar thickness, fold surface free energy and the work of chain folding during isothermal crystallization were evaluated from the analysis of the crystallization kinetics data using Avrami, Hoffman-Week and Lauritzen-Hoffman theories, also supports the same.

Metastable II-VI sulphides: Growth, characterization and stability

[J].

Recent developments on molten salt synthesis of inorganic nanomaterials: a review

[J].

Compositional, structural, and optical study of nanocrystalline ZnS thin films prepared by a new chemical bath deposition route

[J].

Imperfect oriented attachment: dislocation generation in defect-Free nanocrystals

[J].Dislocations are common defects in solids, yet all crystals begin as dislocation-free nuclei. The mechanisms by which dislocations form during early growth are poorly understood. When nanocrystalline materials grow by oriented attachment at crystallographically specific surfaces and there is a small misorientation at the interface, dislocations result. Spiral growth at two or more closely spaced screw dislocations provides a mechanism for generating complex polytypic and polymorphic structures. These results are of fundamental importance to understanding crystal growth.

Oriented attachment of ZnO nanocrystals

[J].

Bulk-sized (~50 μm) faceted wurtzite crystals via non-classical mesocrystalline growth assembly

[J].

Structural phase transformations in annealed cubic ZnS nanocrystals

[J].

Flux growth of ZnS single crystals and their characterization

[J].

Comparing infrared transmission of zinc sulfide nanostructure ceramic produced via hot pressure and spark plasma sintering methods

[J].

Understanding of electronic and optical properties of ZnS with high concentration of point defects induced by hot pressing process: The first-principles calculations

[J].

Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides

[J].

Molten flux growth of cubic zinc sulfide crystals

[J].

Synthesis and investigation of blue and green emissions of ZnS ceramics

[J].

Photoluminescence measurements in the phase transition region of Zn1-x CdxS films

[J].

Effect of porosity and hexagonality on the infrared transmission of spark plasma sintered ZnS ceramics

[J].

Transparent ZnS ceramics by sintering of high purity monodisperse nanopowders

[J].

Fabrication of transparent ZnS ceramic by optimizing the heating rate in spark plasma sintering process

[J].